Hop Exchange

The Hop Trade in Southwark

by Stephen Humphrey

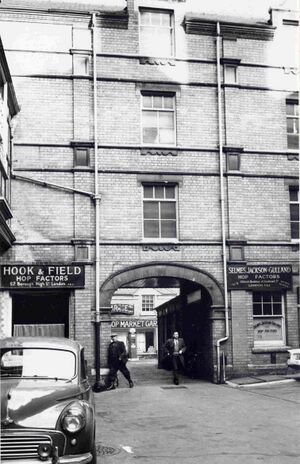

The hop trade was a significant part of Southwark's commercial past until the early 1970s. Innumerable offices and warehouses of hop factors and hop merchants once existed in the Borough High Street and adjoining streets, as large-scale Ordnance Survey maps clearly show.

It would be unthinkable to write of the area's commercial history without mentioning this important trade. But whereas many books and articles have described the part of local people in hop picking, virtually no attention has been given to the hop trade in Southwark itself.

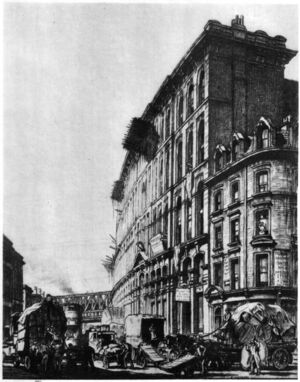

The engraving of 1837 published here shows the Borough High Street, Southwark's main street, looking north past St. George the Martyr Church (Dickens's Little Dorrit Church) towards the cathedral. At first glance it seems to be a normal enough street scene of the day, but a second glance reveals that all the vehicles in the view are wagons carrying hops. In addition, they are emerging from Great Dover Street on the right, part of the main road from Kent's hop gardens, today's A2.

Southwark was for centuries associated with hops, breweries and coaching inns. The inns derived their existence from the fact that Borough High Street and Old London Bridge constituted the only land route into the City from the south until as late as 1750. All the road traffic from Kent, Surrey and Sussex came through Southwark. The proprietors of the inns were rich and influential, often serving as Members of Parliament for the parliamentary borough of Southwark. The best-remembered of these was Harry Bailey, landlord of the Tabard, who led Chaucer's pilgrims in the Canterbury Tales:

‘Befel that in that season on a day In Southwark at the Tabard, as I lay’.

The mediaeval route to Canterbury led you from Borough High Street, via Kent Street, to the Old Kent Road. Kent Street was renamed Tabard Street in 1877. Great Dover Street was what we might call a Georgian by-pass. The two great breweries of Southwark were confusingly both called the Anchor Brewery. One was the original Courage & Co. Ltd, just downstream of Tower Bridge, but first owned by John Courage in 1787, a century before the bridge existed.

The other great brewery, in Park Street near the Borough Market, was much older, going back to the 17th century. In the mid-1700s, Henry Thrale was its owner. He died in 1781, when his friend, Dr. Samuel Johnson, made his famous remark that what was for sale was not ‘a parcel of boilers and vats but the potentiality of growing rich beyond the dreams of avarice’. The year before, during the Gordon Riots, Thrale's manager, John Perkins, had plied the rioters with beer while sending for the troops, and saved the day. The buyers in 1781, the Barclays, made him a partner. The firm remained Barclay, Perkins & Co. Ltd. until it merged with Courage's in 1955. Further breweries in Southwark included Noakes & Co. Ltd in White's Grounds and Jenner's Brewery Ltd in Southwark Bridge Road.

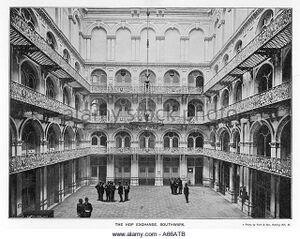

Southwark's hops came from Kent. The symbol of their origin may be seen in the local Hop Exchange: Kent's county arms of a white horse on a red background, repeated endlessly on the galleries of the Exchange's hall. Up to the late 1960s, many local people went to the Kentish hop gardens each autumn to pick the bines. Whole families would stay there for a hard-working holiday. In the far poorer days before the Second World War, the money they earned in Kent provided much-needed extra income.

When the hops had been picked in the autumn, they were traditionally taken to oast-houses for drying, and then packed into what the world might call sacks, but which were known in the trade as pockets.

They typically measured 6 ft. by 2 ft., weighed about one and a half hundredweights and were at one time made of jute, but latterly of synthetic materials. Pockets look rather like the wool sacks that you see on medieval church brasses in the Cotswolds. It was these pockets that were taken to Southwark and stored in the hop warehouses. All this was done under the aegis of middlemen known as hop factors, who acted on behalf of the growers. They made their living by charging the growers commission.

In Southwark, the pockets were sampled, that is to say, a piece weighing about 1 lb. was carefully cut out to act as a sample for potential buyers to inspect. The cutting of a sample was done with a knife more than a foot long, plus a tool called a pair of clams, and a trimming gauge. Thick brown paper was folded round the sample, secured with brass chair-nails. Samples from a particular grower were then strung together with waxed hemp. All this has always been normal in the hop trade and does not relate just to Southwark's past.

The hop factors had showrooms in Southwark, where the samples were once inspected under natural light, despite the inspections being chiefly needed in February and March, when gloom is plentiful; artificial light was not used until well into the 20th century. The buyers in these showrooms were the hop merchants, another set of middlemen who acted on behalf of the brewers. The settlement of accounts came in about April. The factors and the merchants may be compared with the brokers and jobbers in the Stock Exchange in the days of open outcry. They were formed into partnerships for most of their existence, as in the cases of stockbrokers, surveyors and solicitors.

Hop warehouses in Southwark could be substantial buildings. The biggest firm of hop merchants, Wigan's, had several warehouses. In 1864, in the newly-laid out Southwark Street, the firm commissioned R.P. Pope, an architect who had a thriving local commercial practice, to build a warehouse at No. 61 capable of holding 10,000 pockets and having a facility to load and unload four wagons at one time under cover. But even more storage was needed. So in 1868, when a body called the Hop Planters' Joint Stock Company went into liquidation, its property at No.15 Southwark Street was bought by Wigan's, and was massively extended towards the Charing Cross railway viaduct. This immense warehouse empire came in an era when Excise figures show that the annual crop regularly reached between 500,000 and 600,000 cwts., and as much as 797,000 cwts. in 1855.

The firm ran a cricket team, of which it was inordinately proud, and one advertisement for staff in 1903 included the line, ‘only cricketers need apply’. The firm's head for some decades was Sir Frederick Wigan, one of Victorian Southwark's merchant princes. He acted as Honorary Treasurer of St. Saviour's Church when it was being recast as Southwark Cathedral at the beginning of the 20th century, and appeared to have given a great part of the money himself. Numerous substantial fittings in the cathedral were provided by him.

Prices of hops in the mid-20th century were set largely by the Hops Marketing Board, which originated in 1932, following the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1931. After the Second World War, the board effectively swallowed up the hop factors. Further changes took place in that period, too. Warehouses were built at Paddock Wood in Kent rather than in Southwark to replace those that had been bombed; hop pellets and concentrates came into widespread use; and the demand for hops declined by almost half between 1950 and 1980. There was a trend away from the aroma hops such as goldings and fuggles towards the new high-alpha varieties, which meant that brewers needed fewer hops, and the trend for less bitter and more lager had the same effect. Exports diminished as countries such as Australia and South Africa grew their own hops. Eventually, there was more or less world overproduction.

During the war, no fewer than 25 out of the 37 Southwark hop warehouses were destroyed, although none belonging to Wigan's was lost.

Accession to the E.E.C. in 1973 brought in free trade in hops, ending the restrictions on imports, especially from Germany. Overnight, it seemed, the hop merchants packed their bags in Southwark and re-grouped at Paddock Wood. In fact, the Hops Marketing Board and the Brewers' Society had already made a decision to concentrate the trade's activities at Paddock Wood, adding to the warehousing already there. A fragment of the trade survived locally for a few more years. The firm of Wolton, Biddell remained in Borough High Street until it merged with Wigan's in 1991.

The Hop Exchange in Southwark Street is one great surviving local reminder of the trade. It is the grandest Victorian commercial building in Southwark and without doubt a great asset, but ironically it had less to do with the hop trade than one might think.

It was built as a speculation under the name of the Hop and Malt Exchange in 1866-67, and was designed by R.H. Moore. It was intended to comprise an ornate trading floor and surrounding offices. But the hop factors and hop merchants all had their own premises, and did not need an exchange. Consequently, the building was divided up for general office use and for long was known as Central Buildings. The old name has been revived in recent years. Some hop firms and associated trade organisations did rent offices in the building, but most of the occupiers represented other lines of business. The Exchange suffered a fire on October 20th, 1920, which destroyed the original two upper storeys.

The present building is still very impressive, but the original was far grander, looking faintly like the Colosseum. The great doorway is decorated with reminders of the trade. Just across the road, in Borough High Street, the former premises of W.H. & H. Le May (No. 67) still bear their name and the words, hop factors, as well as carvings of hops. On the wall of the pub at No. 32 (opposite), there is a finely inscribed memorial signed by Omar Ramsden, commemorating the members of the hop trade who fell in the First World War.

The several surviving warehouses in Southwark have been converted into other uses, most notably the great ranges in the yard called Maidstone Buildings, whose very name recalls the source of this once-major local trade.