The Story of General Haynau

The Story of General Haynau

Reproduced from A Draught of Contentment, The Story of the Courage Group by John Pudney

- Back to Barclay, Perkins & Co. Ltd brewery page

The forthrightness of brewery people in particular and of Southwark people in general led to an incident at the Anchor — during Queen Victoria’s reign which had international repercussions.

A certain Baron Julius Jacob Von Haynau arrived in this a country in 1850. An Austrian by birth, he had risen to high rank in the Hapsburg army. In Italy he had been in charge of repressing revolt and he carried out his duties so brutally at Brescia that he had become known as the ‘Hyena of Brescia’. Afterwards he had become dictator of Hungary where his hangings and floggings were even more notorious. His evil reputation had spread throughout Europe when arrived in Britain shortly after his deposition in Hungary. The reason for his visit to a relatively liberal-minded country where he was a. unlikely to be welcomed is unknown; although it is known at least that Lord Palmerston then Foreign Secretary, was critical of his presence.

Haynau went the rounds of a distinguished foreign visitor and in due course arrived in Southwark and signed his name in the visitors’ book at the Anchor, prior to viewing the wonders of the brewery in all its mid-Victorian splendour. But before the ink of his signature was dry, the office clerks were spreading the news of his arrival, shouting “Down with the Austrian butcher.”

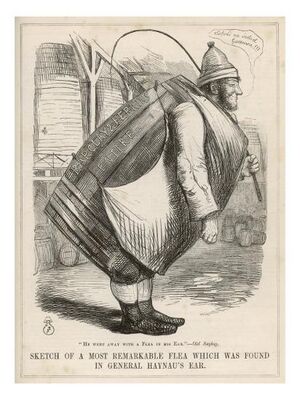

Accounts of what happened vary, but of the severity of the near-lynching there is no doubt. It began in the brewery by somebody dropping a truss of hay on the visitor’s head. Then he was surrounded, pelted and abused by the brewery people who were joined by men and women from the market as he tried to make his escape. Because so many of his own atrocities had been against women, the women of Southwark were particularly ferocious. Haynau fled along Bankside and took refuge in the George public house where, according to some accounts, he was hidden in a dustbin. His life was saved by the multitudinous doors and devious passages of the old inn, which confused his pursuers. Fortunately for him a police rowing galley was alongside and the police managed to rush him on board and row him across the river to safety. “He escaped with his life and lost his moustache” wrote one of the newspapers, referring to his enormous military moustache which had found much favour with characterists. Newspapers and journals, particularly ‘Punch’, took up the incident with relish, and the Barclay, Perkins draymen were the heroes of the hour. The incident, however, did not close with the newspapers’ stories and the retreat of Haynau across the Channel (he died aged 67 in bed in Vienna three years later).

The Austrian Ambassador demanded formal apologies from the British Government. Palmerston’s sympathies were clearly with the draymen. His own view was that the “Ferocious and unmanly treatment of the unfortunate inhabitants of Brescia and of other towns and places in Italy, his savage proclamations to the people of Pesth and his barbarous acts in Hungary excited almost as much disgust in Austria as in England.” Accordingly he first delayed answering the Ambassador and then sent off a letter without waiting for Queen Victoria’s approval of its contents. On receiving the draft, the Queen disapproved very strongly. Palmerston had to defend himself with a note to the Queen: “Viscount Palmerston had put the last paragraph into the answer because he could scarcely have reconciled it to his own feelings and to his sense of public responsibility to have put his name to a note which might be liable to be called for by Parliament, without expressing in it, at least as his personal opinion, a sense of the want of propriety envinced by General Haynau in coming to England at the present moment ... The state of public feeling in this country about General Haynau and his proceedings in Italy and Hungary was perfectly well known ... the brewers’ men were expressing their feelings at what they considered inhuman conduct on the part of General Haynau .-- who was looked upon as a great moral criminal.” The Queen’s irritation was not assuaged. She forwarded Palmerston’s note to the Prime Minister, Lord John Russell: “Lord John will see that Lord Palmerston has not only sent the draft, but passes over in silence her injunction to have a corrected copy given to Baron Keller (The Ambassador), and adds a vituperation against General Haynau which clearly shows that he is not sorry for what has happened, and makes a merit of sympathising with the draymen at the brewery.”

The immediate outcome was that Palmerston, having threatened to resign, had to withdraw the message he had sent to Vienna, and a more apologetic note took its place. But the effect of the draymen’s action lingered on. The Austrians refused to send an official representative to the funeral of the Duke of Wellington two years later in 1852, and by this time the Queen’s views on the incident were more liberal. She expressed surprise that Austria should “slight England in return for what happened to Haynau for his own character.” Public opinion, however, was strongly in sympathy with the Southwark protest. Broadsides and street ballads for many years acclaimed the actions of the draymen. In September 1850 there was even a public meeting at Farringdon Hall in which their “noble conduct” was approved and cheered. When the Italian hero Garibaldi came to London fourteen years later in 1864, one of his most popular gestures was to insist on seeing the “fabrique de biere” where the tyrannical Haynau had been humiliated. At the Anchor Garibaldi toasted the workmen of the world in good Southwark Beer.

THE SOUTHWARK BREWERS AND THE AUSTRIAN BUTCHER by Nicholas Redman, Archivist, Whitbread Plc

The visit of the Austrian Marshal General Haynau to Barclay & Perkins Brewery in 1850, which led to such a “Violent Display of Popular Indignation” that Haynau was lucky to escape with his life, must surely rank as one of the most extraordinary episodes in the history of the British brewing industry. It precipitated an international incident that caused diplomatic complications between England and Austria, and led to Queen Victoria reprimanding the Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston.

Baron von Julius Jakob Haynau, a natural son of William IX, the Elector of Hesse, was born in 1786. He entered the Austrian army and saw service in the Napoleonic Wars. He held a high command in the Italian campaigns of 1848-49 and became prominent for various atrocities, particularly the flogging of women at the taking of Brescia.

In April 1849 the Hungarian parliament deposed the Hapsburgs and elected their leader Louis Kossuth as Governor. He issued a declaration of Hungarian independence and entered Budapest in June in triumph. His rule lasted only a few weeks: the Austrian army under the command of General Haynau crushed the insurrection. Haynau then permitted and exercised the most extreme brutalities in his ruthless suppression of the defeated kingdom. When news of these further cruelties reached England he was nicknamed the “Hyena” by the press.

In 1850 Haynau was deprived of his military command in Hungary, having fallen into disgrace with the Imperial Court in Vienna. He set off on a European tour, eventually reaching London in September.

He seems to have had little idea of the loathing and horror with which he was universally regarded in this country, and proceeded to visit a number of places of interest in the capital. Among these was Barclay & Perkins Brewery at Bankside in Southwark.

Haynau arrived at the brewery with an aide de camp and an interpreter, and although it was realised that they were foreigners, they attracted little notice at first. They signed the visitors’ book and made their way across the brewery yard. The clerks, on inspecting the visitors’ book, discovered at once who was in their midst, and in less than two minutes the word was all round the brewery.

The Marshal and his companions were surrounded by draymen and labourers shouting “Down with the Austrian butcher” and other epithets of rather an alarming nature. A truss of hay was dropped on his head and grain and missiles of every kind hurled at him.

His hat was knocked over his eyes, he was jostled, his clothes were torn, and one of the men seized him by the beard and tried to cut it off. Haynau managed to get back into the street only to be faced by a mob of 500 brewers’ men, coal heavers and others who had heard what was going on. Again he was surrounded, pelted and struck with every available missile, and even dragged along by his moustaches, which were famously long, reaching “nearly down to his shoulders”.

Breaking free Haynau fled frantically along Bankside until he came to the George pub into which he rushed with the mob in full pursuit.

Luckily for Haynau the house was very old fashioned with large numbers of doors and rooms, and his pursuers failed to find him. By now Mrs Benfield, the landlady, alarmed for her own property as well as the Marshal’s life had sent for the police.

With great difficulty the crowd was dispersed and Haynau brought out of the house. The police then got him into one of their boats, and rowed him out of harm’s way, up the river Thames.

Barclay’s were said to be “very indignant” at the conduct of their men and suspended all hands to discover who the ring-leaders were. But there was no doubt where the sympathy of the public lay.

At the official level however the view was not quite so lenient. The Austrian ambassador grew so impatient at the delay in answering his letter on the matter, that Lord Palmerston wrote a reply without waiting for Queen Victoria’s approval. This went to Vienna. Victoria having at last received a copy of the letter objected to the terms Palmerston had used and asked for the last paragraph to be altered.

Palmerston in his reply to the Queen said: “The state of public feeling in this country about General Haynau and his proceedings in Italy and Hungary was perfectly well known. The brewers’ men were expressing their feelings at what they considered inhuman conduct on the part of General Haynau who was looked on as a great moral criminal. His ferocious and unmanly treatment of the unfortunate inhabitants of Brescia and other towns in Italy, his savage proclamations to the people of Pesth and his barbarous acts in Hungary excited almost as much disgust in Austria as in England”.

The Queen sent Palmerston’s letter to the Prime Minister Lord John Russell pointing out that Palmerston had not altered the last paragraph as she had asked, and saying that “his vituperation against Haynau clearly shows he is not sorry for what happened, and makes a merit of sympathising with the draymen at the brewery”.

In the end Victoria administered a severe rebuke to Palmerston. Russell insisted on an amended note, and after threatening resignation Palmerston submitted.

The episode gave rise to popular songs and broadsheets filled with appropriate puns about the actions of the “stout sons of freedom” in the glorious battle of Bankside.

A typical verse reads:- “Jolly boys, who brew porter for Barclay and Perkins, The prime London stout of our cans and our firkins, Here’s a health, English hearts, whate’er may betide For the dose you gave Haynau along the Bankside.”

Haynau returned to Vienna where he died on 14th March 1853. Memories of the affair lived on. The Austrians sent no representative to the funeral of the Duke of Wellington in 1852 as a protest, and when Garibaldi came to London in 1864, he asked to see the brewery where “the men flogged Haynau” and drank a toast there to the workmen of the world.